Reminders for Humans is a monthly series that explores a natural phenomena, and how I’m applying its wisdom to my own human life. I’m a scientist by training, and a gushy poet by nature. Expect both.

“Behind every successful elephant dynasty, you will find a wise matriarch who carries a treasure trove of knowledge”

- Angela Sheldrick, “The Makings of a Matriarch”

I’m big on the Notes app.

A notebook and pen is preferred, of course. But in their stead, the iPhone Notes app does the trick. I have notes dedicated to original quotes from various people and places - mostly, to laugh at later. Quotes are a strange language of love that I’m fluent in.

There is a note for a group of rugby friends, who have fantastic ideas at 2am while camping.

One for originals from work calls. Another for a bachelorette party in Palm Springs. One for the overheard-in-public moments I’ve been truly blessed to witness.

There's a note from the solo trip I took to Italy, filled with the grammatically wrong but incredible phrases and questions of native-Italian speakers: “The heavy bug that stinks when you crush it. What is the name?”

There is a note for the kids at the school district I used to work at. They are all over the board in levels of ludicrous, but my favorite came after I gave a presentation on ocean plastic pollution to an assembly of second-graders. I asked if there were any questions- a choice I would (quickly) learn to never repeat. Hands shot up, hot with the unreserved confidence of being seven. I picked a boy with dark brown hair in the front row. I crouched to his level and extended the microphone. “Yes, what’s your question?” I said. He grabbed it with meaty fingers, made direct eye-contact with me, and put lips to metal:

“My mom’s name is Sarah.”

(Not a question.)

However. My favorite is the amalgamation of quotes from my family - particularly, the giant, East-coast, Irish-Catholic brood I marinated in for most of my childhood. Chief among them, the originals of my Grandma, Mary Rose.

Some context.

Grandma, or “MRQ” as she was known about town, had nine children, a storied career, and a helluva personality. She was a nurse at the hospital next door to their first house, and as legend goes, every time her water broke, she would walk over and ask for a window room facing their backyard- so she could, once successful, hold up the newborn baby in the window and holler its name for her other kids to hear. She had twenty-one immediate grandchildren, countless nieces and nephews. She kept herself busy after her husband died: went back to school for her degree in communications and gerontology; went to St John’s Roman Catholic mass multiple times a week; played the piano and read every new book at the library; started a book club and volunteering group for the elder women in our small hometown. MRQ was a force of nature. No question about it. She deserves a biopic, which this essay could simply not accomplish. She wasn’t one to offer her story unprompted (but prompted, she would happily share - sparing no details, forgetting no names or dates.) She had been through a lot, she’d seen a lot, and you would only know this by what she said to you. A week ago, she died at 94.

I’m told by my father that, in her final days, as she was carried out on a stretcher from her home to the ambulance, she told the paramedics to “pick up that garbage on the floor, will you?”

Grandma entered this world a manager. A delegator. Inherently skilled in ways that many of us people-pleasing wussies could never dream of. While off at the hospital or volunteering at the church, she left her children lists of chores to accomplish in her absence (paint the garage door, mow the lawn, do the laundry, do the dishes, Rob- make breakfast, Jim- make dinner. Clean the basement, then clean the attic, then start on the basement again.) The list had to be complete before anyone could run off, or there would be hell to pay. Their friends knew the drill. They would flock to the house and help the siblings complete their tasks, so they could all go play baseball.

Decades later, on our occasional half-days of school, my sister and I would walk to Grandma’s apartment to be supervised for the few hours before our parents picked us up. We’d promptly be put to work. “Be a sweetie and bag up those newspapers over there.” “When you’re done taking the trash out, why don’t you wash the windows? I have a bucket under the sink.” “You’re sitting. Here’s some corn to shuck.” My mom tells the story of the first time she met Grandma; she nervously introduced herself while MRQ ran the kitchen of the cottage. “It’s nice to meet you, dear.” Grandma said. “Now, could you marry the ketchup bottles?”

Once, she entered a room of her grandchildren, where someone foolishly asked “Grandma, who’s your favorite grandkid?” She paused for a minute, and picked one of my cousins “David.”

“Aw, thanks Grandma!” David said as he left through the screen door, clearly buoyed by the compliment . Grandma looked at the rest of us once it slammed shut and he was out of earshot, “Not really, kids” she paused. “It’s actually Kelly.”

(Kelly was our much-older cousin. She lived on the opposite side of the country, never visited, and definitely never took out Grandma’s garbage.)

She was nothing if not prudent. Phone calls were kept to a tight fifteen minutes; she ended them, always, mid-conversation with a “well, I’ll let you get going!” For many years, I played a one-sided game in which, every time we signed off, I’d say “Bye Grandma! I love you!” The game: would she say it back? (Usually, no.)

“Okay honey. I’m praying for ya.” or

“Okay, God Bless.”

“Okay. Bye-bye.”

“Okay honey, you take care.”

I scored a few “I love you too”s over the course of my lifetime, but it was not habituated into her lexicon like it was mine. She was much more likely to pray for you; or to have just prayed for you before you called. Or to pray for you that night (and every night, you know.)

I love you too was simply not as prudent or helpful as praying for you, or telling you to take care.

When Grandma died, our extended family flocked back to Western New York like locusts.

Intimate and Deeply Complex Social Bonds

It’s counterintuitive. Absolutely.

But in many ways, elephants and humans have a lot in common. So much so, that some researchers are studying the aging processes of elephants, and their ability to live nearly as long as we do without succumbing to the neurodegenerative diseases that plague so many of our beloved elders. (1)

Elephants lead deeply intimate, complex social lives. They have a vast capacity for long-term and social memory, recognizing peers and family members after extended time apart; remembering paths, landscapes, and places of their youth. They have long gestational periods at 22 months, and typically raise their calves to a few years old before reproducing again. Elephants can live for seven decades. They have a language we are just beginning to understand, after a recent study showed results indicating that they call one another by, and respond to, unique names (2)

There have been studied observations of elephant behavior that resembles social cooperation, empathy, consolation, and mourning. (1)

When a herd member dies, elephants are known to visit the body for days and weeks after its passing, almost like a wake and funeral procession. And it’s not just immediate family or connections that come to visit and inspect, but otherwise unrelated elephants and those from neighboring communities. Researchers followed a particular herd for over 20 years, and when the herd’s matriarch, a 55 year-old female named Victoria died, they observed behavior among the herd that - I personally - would call mourning.

“Several elephants huddled around the body, recalls ecologist Shifra Goldenberg, who was observing the animals with colleagues that day. She noticed that Malasso, a 14-year-old bull, was one of the last to leave. Victoria was his mother. … Another elephant to linger was a 10-year-old named Noor. She was Victoria’s youngest daughter, and when she finally plodded away, the temporal glands on each side of her head were streaming liquid: a reaction linked to stress, fear and aggression.” (3) Similar responses have been witnessed after the loss of calves and young adults (5), and at calves delivered stillborn.

‘“As this paper shows, where there are elephants being intensively observed, there is clear recognition of behavioural responses to loss,” says Phyllis Lee, an evolutionary behaviourist at the University of Stirling. … “Loss is a phenomenon common to sentient animals, including humans.”’ (3)

In this video, we see at least four elephants standing around the remains of Victoria, almost 3 weeks after her death. These are not her family members. The narrating biologist notes how unusual this is. “Elephants don’t waste a lot of time in terms of feeding” she says. “They have to feed for about 20 hours a day, just to get all the nutrients that they need.”

To see so many visitors standing around Victoria’s body for extended amounts of time- not resting, not feeding- but seeming to just be with her is something we don’t quite understand. We can’t know how an elephant mourns, or if it mourns. But these inclinations feel familiar to our own.

“This may explain why a bull named Omtata spent eight minutes sniffing Victoria’s body and the dirt around it. Or why the elephants continued to interact with her body even after rangers had removed the tusks to secure them from poachers, or after scavengers had reduced the carcass to skin and bones. Or why studies have found that elephants show extreme interest in skulls, jaws and other bones from their own species while paying little mind to bones from cape buffaloes or giraffes.The same is true of elephant tusks, which are important focal points for elephants. Goldenberg and Wittemyer documented an elephant carrying a disarticulated tusk for more than three miles.

“They are touching each other’s tusks all the time,” Goldenberg says. “And they tend to show disproportionate interest in tusks relative to other bones.”’ (3)

The question is - why?

Making a Matriarch

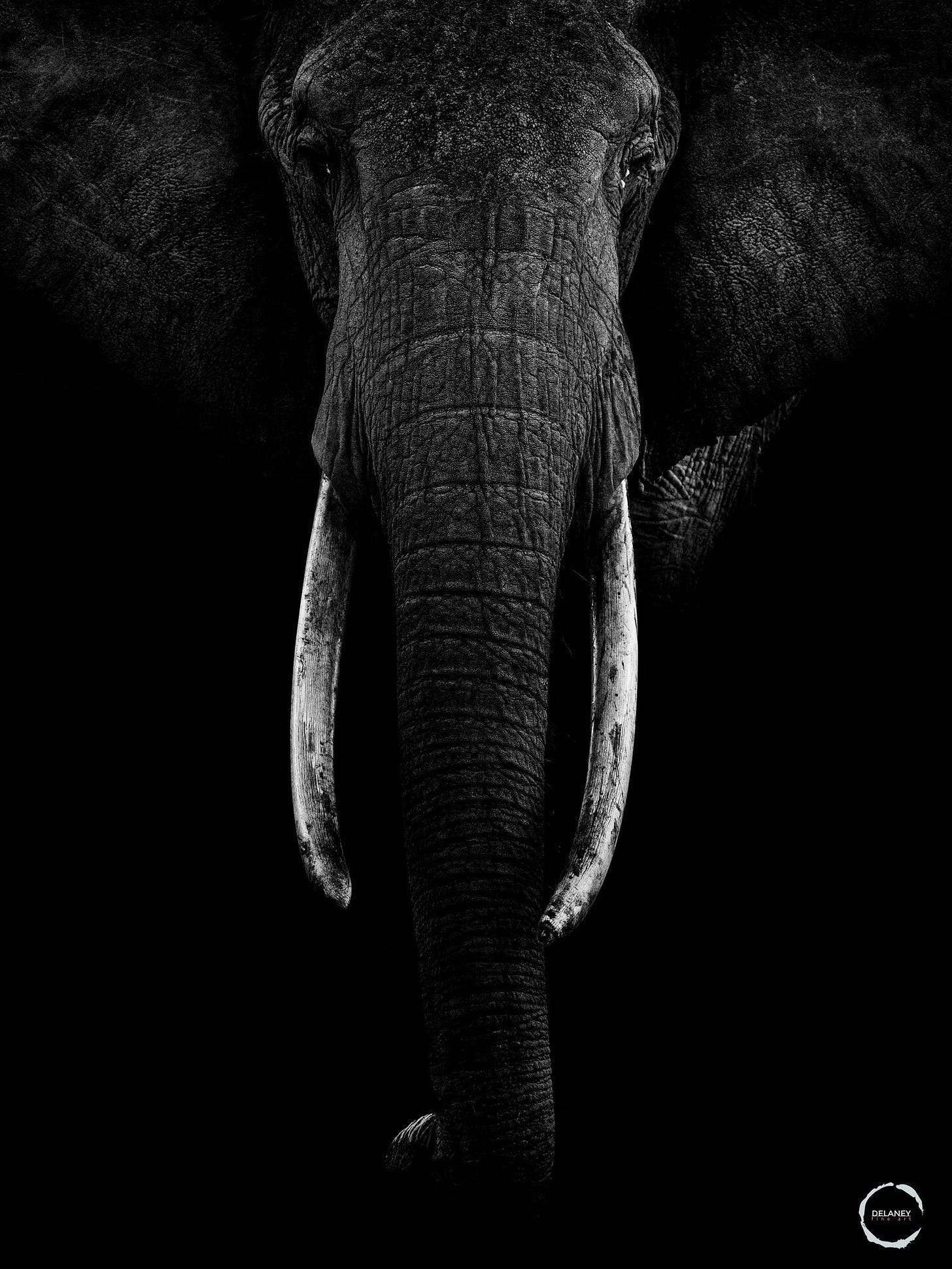

Elephant herds are led by a matriarch.

The herd itself is comprised entirely of the females (called cows) of the same family and their young calves. Mothers and daughters have extremely close bonds, and live together over the course of their lives.

Male elephants (bulls) grow up amongst the mother herd, and once they reach between 10 and 20 years old, they leave and live as loners, or join up with their male counterparts and extended family, who are in their own all-male group and usually following the female herd from a distance. Sometimes, older and experienced bulls will act as mentors for young bulls, leading their all-male groups. Typically, adult bulls and cows only interact when mating. The entire family of elephants, then- broken up into female and male groups of varying sizes- are led by a matriarch, typically (but not always) the oldest female in the family.

Within the female herd, raising calves is a community effort. Referred to as allomothers, other juvenile and adult females also care for calves that aren’t their own. Picture a village of mothers and aunties, working together to keep their youngest, newest family members alive. Idyllic. This keeps the distribution of labor less concentrated, and in some ways, allows for calves to learn more than if they only had one caretaker to provide for them. You could argue that this approach may benefit the species, by creating more well-rounded, experienced, resilient adults.

Elephants partake in a unique method of socialization, called fission-fusion. This means that throughout a given day, a herd may break apart into smaller groups (fission) and rejoin (fusion) several times. The group’s size is always changing. In practice, this can mean that “an adult female elephant might start the day feeding with 12 to 15 individuals, be part of a group of 25 by mid-morning, and 100 at midday, then go back to a family of 12 in the afternoon, and finally settle for the night with just her dependent offspring.” (6) Fission-Fusion processes are somewhat rare in the animal kingdom, but are also seen in communities of primates and, of course, humans.

Despite the variance of the group’s makeup throughout the days, weeks, years - what stays consistent is the leader of the herd.

Not every female is cut out for the role. Researchers are also observing and codifying some behavioral aspects across matriarchs, in the hopes of understanding what, in our words, the most common personality traits and characteristics of chosen matriarchs. But perhaps the most valuable trait is age: the eldest females are the most likely to assume the leadership position for their herd. It’s unclear precisely why this is, but there are many biologists studying this - it’s a question whose answers may make a critical difference in protecting this species as a whole.

Various studies have shown the same interesting results: herds led by older and more experienced matriarchs have the highest likelihood of survival.

Wisdom of Age

The matriarch is critical to the survival of her family, and the species as a whole. Her job is to ensure the herd is fed and protected - no small feat - and to serve as its trusted resource; embodying the wisdom and experience she’s gained over her lifetime.

The presence of elder matriarchs in a population of African Elephants can indicate a greater likelihood of survival. Why? The wisdom of years. It’s speculated that the older a leader, the more historic knowledge, wisdom, and memory of the landscape lives inside of them.

"Our findings seem to support the hypothesis that older females with knowledge of distant resources become crucial to the survival of herds during periods of extreme climatic events." said Wildlife Conservation Society researcher Dr. Charles Foley. (7)

“Studies in Amboseli have revealed that families with older, larger matriarchs range over larger areas during droughts, apparently because these females better remember the location of food and water resources. “The matriarch has a very strong influence on what everybody does,” [Vicki Fishlock, a resident scientist with the AERP] says, though exactly how they communicate their will to the group remains a mystery.” (6)

“The idea that groups led by older matriarchs might have a survival advantage is supported by a study of elephants in Tangarire National Park in Tanzania. In 1993, infant elephant death rates rose from an annual average of just 2 percent to around 20 percent during a nine-month period of drought. With their dry-season refuge parched, some family groups stayed in the park while others made off for places unknown. Young mothers were far more likely than older ones to stay put and to lose calves, and families that migrated out of the park had lower mortality than those that remained. Since matriarchs lead long-distance group movements, this suggests that older females provide a survival advantage for their extended family.” (6)

It’s logical, really. The older a matriarch is, the more memories, the more data she has to consider when assessing a situation: deciding where to lead her group in search for food and water; which types of lion roars (their main predator, aside from humans) are the most dangerous and worth reacting to; when to initiate her herd into a tight huddle to protect the young from nearby threats. Her long life experience benefits the entire herd, but in the macro sense, her species.

Losing a Matriarch

The two most significant threats to African Elephants are climate change and humans. A warming climate leads to more extreme weather patterns- extending droughts for months beyond historical averages, peaking the temperature year-round, affecting available water and food supply.

Asian elephants, by contrast, have less structured matriarchal roles - an interesting difference that biologists are still learning more about. One hypothesis is that their herd structure does not rely heavily on the leadership of a chosen matriarch because resources like food and water are much more abundant, and the climate more predictable in their habitats.(8) Compared to their distant relatives, we can imagine that African Elephants’ inclination towards clear leadership is likely an evolutionary advantage - one that significantly benefits their chances at survival through the stored memories of decades past, still alive in their matriarchal leaders.

Poaching, while down from the peak rates in 2011 (when a recorded 40,000 elephants were illegally killed in one year) is still a major threat to elephants, and elders in particular. The black market ivory trade is still a lucrative business, albeit illicit, and the oldest elephants have the longest tusks: making these community leaders the most likely targets for slaughter.

While researching social bonds and structures within herds, I learned something fascinating and devastating (sorry); another way in which our species mirror one another. It’s suspected that elephants, similar to humans, can suffer from a form of PTSD (10.) Their strong social ties and long-term memory make them especially susceptible to psychological trauma; particularly at the tragic loss of their herd and family members.

From a 2005 essay in Nature (10):

“The air explodes with the sound of high-powered rifles and the startled infant watches his family fall to the ground, the image seared into his memory. He and other orphans are then transported to distant locales to start new lives. Ten years later, the teenaged orphans begin a killing rampage, leaving more than a hundred victims. ..

A scene describing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in Kosovo or Rwanda? The similarities are striking — but here, the teenagers are young elephants and the victims, rhinoceroses.”

This is the story of teenage elephants who, after witnessing and surviving the poaching of their mothers and family, became orphaned and later, uncharacteristically violent: killing over 100 rhinoceroses - “an aberrant behavior for elephants” (1). “Male elephants with PTSD were responsible for 90% of all male elephant deaths in their community, compared with 6% in relatively unstressed communities.” (1).

While elephant societies have ritualistic behaviors and patterns that appear to be methodologies for moving through mourning, grief, and loss, poaching continues to decimate family structures and, in some ways, the passing-down of these practices across generations.

“Elephant society in Africa has been decimated by mass deaths and social breakdown from poaching, culls and habitat loss. From an estimated ten million elephants in the early 1900s, there are only half a million left today. Wild elephants are displaying symptoms associated with human PTSD: abnormal startle response, depression, unpredictable asocial behaviour and hyperaggression.

Culls and illegal poaching have fragmented these patterns of social attachment by eliminating the supportive stratum of the matriarch and older female caretakers (allomothers). .. Calves witnessing culls and those raised by young, inexperienced mothers are high-risk candidates for later disorders, including an inability to regulate stress-reactive aggressive states.”

We are learning more every day about the impacts of trauma on human neurobiology, and its associated behavioral implications. This story scratches the surface of the same behavioral implications, mirrored in young elephants.

A matriarch’s presence is critical, and her absence- on even the most peaceful of terms- is devastating.

Which way should I go?

There are some people whose presence carries a different kind of value.

It is not the cheap sort, inherent to our day-to-day grind: their essence cannot be simplified into a shiny container, a list of accomplishments, an impressive job title. There is something about this person that is hard to put your finger on; an esoteric kind of presence. A presence that can quietly rearrange your insides.

MRQ was one of those people. She knew a lot, but did not say it all. She had seen the best and worst of life, and remained even-keeled. She had lost some of the most important people in her life to disease and misfortune. She had suffered and suffered but also loved and lived and explored.

You know a matriarch when you feel her; not when you see her. Not everyone really has what it takes. She has a way of bending the energy of the room she’s in; adjusting the way reality is seen. She knows when to speak up and stay silent; when to drop a hint, or give away the ending. She has experience - the kind that’s most valuable: life experience. It is a gift to know her. It is a gift to allow yourself to be led by her, even if only for a season.

Grandma remembered everything: She knew every cousin and second cousin, their jobs and where they grew up, their spouses names and where they grew up. She could recite the family tree of nearly anyone in our hometown. Til the very end, she could. In this way, she kept our family alive. She kept our history, our ancestors, our relatives who had died many years before her - still with us, still a part of us. And us, still a part of them.

Funny quips and managerial anecdotes weren’t all we learned from her. In her older years, she would ask us about our lives, then let us ramble in stories and ideas, dreams and goals, fears and heartaches - all while she quietly nodded along, or chuckled. Holding us in her attention. “I’d rather a good laugh than a good cry” she’d say. And “better to stay quiet and thought a fool, than open your mouth and prove it.” Each St. Patrick’s Day, she led us in “When Irish Eyes are Smiling.” My aunts and uncles sang it to her on her last day on Earth.

Finding resources is not something to think twice about. Our modern world continues to find ways to make the process of searching (and finding) easier – requiring as little labor as possible. In some ways then, it’s hard to really appreciate these skills for the miracles that they are. With nothing to aid you in finding food and water in an unknown wilderness, our odds are next to zero. (At least, mine are. I’ll speak for myself.)

Which way should I go?

Imagine you’re dropped, ex-machina style, into the African savanna. No phone, no GPS. Now go find water. Go find food. Keep yourself alive and safe from predators, from the elements. Interpret the sights, sounds, smells around you. Live inside the not knowing, maybe for days or weeks. Survive. Raise a family.

You should feel humbled at the thought of this scenario. You should feel the opposite of how you feel inside of our hyper-individualistic, self-reliant, instant-gratification universe. You should hope to God some giant, wrinkled angel may plod along, ground shaking around her, to guide you. You should feel an exhausted kind of smallness and awe and gratitude for this silent leader, a soft elder to show you the dusty, traveled paths of her ancestors.

Wisdom is not a sound bite. It’s not an excerpted quote, cut and pasted into a square on your feed. Wisdom takes time to accumulate, and it takes time to absorb. It’s shades of gray, not black-and-white. Wisdom is adjusting to the environment and circumstances; it’s fluid and dynamic; it changes and morphs based on the situation; it’s quiet and considered. It does not arrive, but is assembled over the course of a lifetime.

Before we had spoken language and cuneiform and the printing press, we had wisdom. We had story, feeling, perception. We relied on wayfinders and trackers and elders. This was the most valued of currency. We valued memory that was stored in the body. We learned to value that memory in ourselves.

The value of a matriarch is the wisdom of someone who remembers the path. That kind of wisdom is only created through memory and time – two elements we absolutely cannot get our arms around, though we’d like to think we can. Knowledge transfer, emotional bonds, presence. Wisdom from age and experience is not a commodity to acquire, trade, sell. It is not something you can hoard, learn through a Google search or podcast, go back to school for, or otherwise purchase.

The cost of it is time.

Its key ingredient is living attentively.

I know the mind can be fleeting and fickle. My googling muscles are strong, but is my memory? Is the compass inside of me?

I grasp at these things as best as I can. I write down quotes, maybe to remember these moments in my body again. To remember what I really mean by “My friend Nick is a hoot “ or “That teaching job was ludicrous but amazing“ or “My grandma was a born manager. Hilarious. One-of-a-kind.“

Before we had language, we had a cranky grandma. She learned from her cranky grandma, and so on and so on, for all of time. We may have resented their insistence for doing things a certain way – likely we did resent this (just like cranky Grandma did when she was young.) But in time a kind of compass grew in us, too. We learned how to notice. We learned how to navigate. The wisdom of other bodies somehow translated into our own.

This is what’s lost when we lose our matriarchs. We lose the first chain in the generation, the source of knowledge from the past. Janus with two faces: who can see into the past and into the future. We lose the link that connects our living bloodline to the world of dust and bones; to those paths and people we can never access again.

What is the lesson?

Watching the herd stand vigil at the body of their matriarch hits the same sore corner of my heart that didn’t want to leave the cemetery that Friday. The grass was too green, the sun too bright, the air blessedly and unusually absent of the usual humidity, thick as soup. Our family- her family- stood in vigil en masse, outfit in black. It was too beautiful to leave yet, her pink velvet coffin still above-ground.

The same soft part of my heart that read and reread the obituary- not from a place of anguish, but of seeking familiarity. Or maybe remembering. Or maybe to soak her in a little more. Running my trunk over her tusks.

My lesson is to remember that this inclination lives in an animal body like mine. Just as it lives in the animal body of elephants. Every elephant. Every human. Social softies like us.

Victoria, the 55-year old matriarch, died of natural causes. She was not hunted, poached, chased, or starved. “Certainly, it’s sad” says George Wittemyer, the biologist who followed Victoria and her herd for over 20 years. “But this is what we would hope for, that elephants can live out their lives and die peacefully, in an area where they’re not being hunted.”

“We got to watch her die naturally, in a beautiful part of the park, with her family around her.” (3.)

No doubt, just after telling someone to pick up that garbage on the floor.

Thank you for reading. It means a lot to me that you do.

I am still deciding whether I believe in allowing comments on my posts. I am committed to being a better protector of my heart and dopamine levels, while still sharing the art that I love to make. Regardless of my digital accessibility, please know- I am truly, truly glad you’re here.

xoxo, Sarah

Sources:

Aging: What We Can Learn From Elephants. Frontiers in Aging, 2021

Elephants call each other by name, study finds. The Guardian, 2024

Larger than life: Why the death of an elephant is not the end of the story. The Independent, 2020.

Rare Footage: Wild Elephants “Mourn” Their Dead. National Geographic

What elephants can teach us about the importance of female leadership. Washington Post, 2014

Scientists find elephant memories may hold key to survival. American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), 2008

Asian elephant herds lack clear matriarchs, strict hierarchies: new study. Mongabay, 2016

The Makings of a Matriarch. Sheldrick Wildlife Trust, 2020.

Elephant Breakdown. Nature, 2005.