Reminders for Humans is a monthly series that explores a natural phenomena, and how I’m applying its wisdom to my own human life. I’m a scientist by training, and a gushy poet by nature. Expect both.

This is Chapter 4 of an ongoing series about my time volunteering at a wildlife sanctuary in Bolivia. Read Chapters 1-3 here.

“Perfectionism is the voice of the oppressor, the enemy of the people. It will keep you cramped and insane your whole life.”

— Anne Lamott, Bird by Bird

Reminders for Humans:

One way to keep yourself safe is to mimic the sounds of predators and danger.

The instinct to adopt others’ venom is shared between humans and macaws. We threaten others with the precise kind of poison that has hurt us. We use our advanced intelligence to mask our vulnerability with familiar sounds, with borrowed weapons.

We use this tactic on others. We use this tactic on ourselves.

Josefina does not like me.

I only think about this constantly.

To be fair, we got off on the wrong foot.

The aviary was my next assignment after Especiales. I looked forward to it- I love birds and suspected caring for them would be easier than lugging heavy bowls of vegetables and carrying buckets of water for miles on end. By volume of buckets to carry, I was right. That it would be easier, I was wrong.

On the first day of work I arrived and waited outside the gates of the area for the ranger. In the other areas, this was a clear requirement: you do not enter without the ranger. You don’t do anything without the ranger. This is to make sure you don’t get injured or killed or otherwise fuck everything up.

I stood outside the gates sneaking peeks at the rainbow of feathers inside, hearing the screeching and caws and the occasional “hola”, which sounded eerily human.

Amused, I answered.

“Hola” I cooed back. More caws and croaks and hola’s in response. There were at least sixty of the colorful birds: small green parrots and strapping macaws clothed in primary colors.

The ranger, Josefina, showed up five minutes late. I smiled my biggest smile and said “Buen dia” and followed her lead through the gates. When we got to the toolshed to begin work, I said the cautionary sentence I had memorized in Spanish: “I can understand some words, but please speak slowly.” She nodded at me, lips puckered politely. Then proceeded to speak at a full clip. (At first I assumed that I had said the sentence wrong. In hindsight, this seems less likely than her decision to disregard the request altogether.)

She handed me a bucket of soapy water and a handheld scrubbing brush, then pointed to the slabs of concrete that littered the aviary ground- each positioned beneath a feeding area. “Tuuuuu..” she said in slow Spanish, pointing at me, “liiimpias” pantomiming scrubbing motions, “aquiii” motioning towards the nearest block. You clean here. She crouched down, pointing dramatically at the bird shit splotched across the pockmarked rock. “Here” she said “and here” pointing each time at a different white and black pile. She looked up at me. “Entiendes?” she cocked her head.

“Si” I said. “Entiendes.” Yes, I understand.

I wasn’t sure what work I expected to do in the aviary at 8 am, freshly awake and ready for the day, but it wasn’t this.

“Bien.” She rose to her feet.

Now understanding the assignment, I reconsidered my tools. My fingers were blistered and worn from the prior days of work, cut in at least two places. I remembered the empty first aid kit and the general lack of concern for injuries amongst the staff that I had noticed thus far. Josefina was already walking away in her bright pink rubber boots, matching sun hat, and long rubber gloves. I hated the idea of asking for help, but the potential downside of further injuries seemed like a worse fate.

“Um..” I clambered, racking my head for Spanish vocabulary that never came. She turned around. “Are there… gloves?” I mimed putting gloves on, pointing at my hands, and then at her gloved, yellow fingers. She considered me and blinked, then sighed and turned back towards the toolshed. She opened a cabinet and grabbed another pair of hidden yellow gloves, walked back and handed them to me begrudgingly. “Gracias!” I said about fourteen times. She walked away.

She was really just going to let me clean bird shit with my bare hands?

Expectations were becoming clear.

I should not wait for a safety training- or any training. If I got hurt, that was on me. If I contracted the avian flu from scrubbing bird shit off the concrete with open wounds, that was a Me Problem. No one was going to look out for my well being, least of all Josefina.

I snapped on the gloves and got started.

It was pretty straightforward: clean the concrete slabs under the feeding tables; where the birds would perch along silver handrails, eat, drink, and poop their pants freely. I squatted on the ground, using one hand for balance and the other to bring the dripping brush against the speckled spots - pushing the piles of excrement off and onto the dusty ground. It took about fourteen seconds before my first mistake, when I scrubbed at the wrong angle and felt the brush’s wet mist, water-and-shit-combo, ricochet across my face. I froze. Brought my sleeve up to my cheek and my (luckily) closed mouth and wiped it away.

Mask, I noted mentally. I’d grab it after breakfast.

Throughout the entire enclosure there were probably twenty feeding tables and foundation slabs of rock underneath, each a 2 by 10 foot rectangle. By the time I reached the last, it had been forty-five minutes. I was warm with effort and pleased with my work. I returned to ask what else she needed me to do, and prepared myself for praise- maybe even a hint of happy-surprise at how quickly I’d finished it all; perhaps even a real smile.

“Esta bien?” I asked. Is it good?

Josefina looked up at me, then around us at the ground. “No” she said, shaking her head and standing up “no, no, no.” Chuckling to herself, she walked right past the now-clean rectangle slabs without a comment. My heart sank. At the cobblestone path, which ran the length of the aviary, she pointed down at bird shit on the tiny rocks in formation “here”, she said. She kept walking and pointing. She stopped at another white spot on the wall of chain link fence “here”, then down at a stray rock on the ground “here”, a boulder by the fence “here”. She looked back at me. I sensed she was getting some pleasure from this.

“TODO” she said loudly and slowly, now theatrically dragging her pointer finger in every direction, encircling the entire aviary.

Everything.

The entire aviary. I was supposed to scrub every white spot in the whole place.

Jesus Christ.

I snapped the gloves back on.

At 9, I asked about breakfast, because breakfast started at 9. That was a mistake.

She glared at me (I cannot actually recall a time that she looked at me without glaring). She was carrying a tub of papaya-banana fruit salad on one hip, plopping handfuls of wet fruit on the feeding tables and perches - to the delight of the now-flocking birds. She said something to the effect of she decided when we could eat breakfast - not the clock. Later, as we finally joined everyone else in the dining room for porridge, she pulled aside the only bilingual person at the table, my new friend Anul, and spoke at him in a loud and clearly annoyed tone while he nodded and sheepishly made eye contact with me.

“That was for me, wasn’t it?” I said, after she walked away. “Yeah.” he admitted. “She says you can’t leave early or show up late. That’s not how it works in the aviary.”

My cheeks burned. Four hundred retorts queued themselves up. I didn’t leave early! And I showed up before she did! It’s not my fault we were behind schedule! I know how to work! I’m not flaky! I just scrubbed bird shit off of every surface of a giant birdcage!

Instead, I swallowed hard, my pride lodged squarely in my throat. Those very true and very valid points would make 0 difference now. He was just the messenger.

“Okay, got it. Thanks. Sorry.”

Whatever. I usually found a way to make people like me. Josefina would just be a harder nut to crack, but I had three days. Plenty of time.

Not all of the birds in the aviary could coexist peacefully with one another, so there were separate enclosures throughout. Cleaning and feeding meant moving in and out of these individual enclosures, which meant entering into the unique culture and social hierarchy of each. By the numbers, there were mostly macaws - beautiful birds the size of hawks and covered in vibrant, long feathers - red, yellow, and blue. The rest were smaller birds- green and yellow parrots- that were generally faster and feistier. They were all, as would learn, grudge-holding and wary of strangers.

After breakfast I was walking between sections, closing the gate of the first and entering the main area, when I heard a rustle of wings and felt a swift thump to the back of the head - dislodging my hat and rustling the hair into my face.

“What the..?”

Had I run into a branch?

I looked up and around in confusion. Above me perched a Green Parrot: chirping angrily and quickly, cocking his head back and forth. Probably studying me to determine the next angle of attack.

Not a branch, just a bird. An angry bird. (Sorry.)

A few hours later, the same parrot found me in a different part of the aviary, appearing suddenly on my shoulder, grasping the tan fabric of my work shirt with his clawed feet while flapping his wings with fervor against my back and head. The purpose of such a trick being, I could only imagine, to discomfort me into leaving. Some version of a chaotic attack. I shrugged him off with effort and finally he released the shirt and retreated, though not without more angry chirping.

Shee, shee, CHEEP CHEEP CHEEE.

The birds shrieked nonstop for every minute of every goddamned day. When I say shrieked, I mean it. There were no coo’s, no hoot’s, no whistles, nothing resembling a song. Strictly shrieking. It’s a sound mainly unfamiliar to me and maybe to you, so I’ll give you some examples.

Braachh. BraaachhhHH. Imagine that throaty shriek characteristic of HBO dragons. Now reduce the volume slightly and imagine it coming out of a razor-sharp bird, no bigger than the Stanley canteen you lug around. (Rough translation: Casual. Hey guys. What's going on over on that side? Did you see that guy walking nearby earlier? Weird hat. Anyway. Shit anywhere cool lately?)

Ahh. AHH. AH! AH! AH! Imagine the sound of a small child screaming at the highest pitch available to them, as only small children can. An Emergency Scream. We’re talking shatter-glass pitch. (Rough translation - UM, THE NEW GIRL IS BACK? CAN WE GET EYES ON HER PLEASE?)

Crawwwk. CrAAWk! CRAWWWK. (Angry. Often accompanied by dive-bombing.)

I began to duck instinctively at the sound of flapping wings overhead, feeling a new kind of kinship with field mice. Being in a cage with over sixty birds, this meant I was ducking almost constantly, on-edge at all times; holding my breath for the next thump to the head, shit landing on my shirt, or beak to the hands as I cleaned up papaya remnants from breakfast.

At one point I looked for Josefina, and found her across the enclosure in the cage with the sensitive birds.

She stood next to the feeding table, tenderly scratching the tiny blue feathers along the back of a Macaw’s head. It leaned in towards her, rotating its head for better angles, calm and content. She cooed something and stroked the perfect cerulean feathers of his back and wings. I watched with envy.

I had already survived the first three days at the sanctuary, arguably the most difficult in terms of getting acclimated. This felt like a major accomplishment all by itself. I’d been humbled, or more like pummeled, into acceptance, over and over. Enough cold showers will remind you: comfort is a privilege. And the consistent absence of comfort will scrub away the expectation that you deserve it.

I approached the aviary the same way I’d tried to approach everything on this trip: with an open mind, and the expectation that I would probably get it wrong. Two very difficult things for a control freak to summon, yet two critical provisions to pack on any trip to a new place with a language barrier and an unfamiliar culture. But in the aviary, I was guzzling down my reserves of these provisions faster than usual.

On day 2, I arrived early and let myself into the toolshed. Fumbling around for supplies, I found a printed and laminated list of tasks and instructions behind the rack of cleaning tools - evidently written for volunteers like me. There was even an English version on the opposite side. I exclaimed and nearly jumped for joy. Finally, a life raft of something familiar: English, guidelines, specific direction. My perfectionism was reunited with its dearest friend The Rules. I memorized the schedule in totality: sweep, deep clean, feed breakfast, clean up breakfast, scrub the pools, feed lunch, replace water, clean lunch, haul out the compost, sweep again, lock up.

Now that I knew what to do, I could excel. I wouldn’t need to wait for Josefina to tell me what was next, or drown translating her raging river of Spanish. I would regain her trust. I would be a dutiful little worker; correct and dependable. Things were finally looking up.

When Josefina arrived, I was on step 1: sweeping. I waved and smiled at her as she walked in, Buen dia! She gave a polite wave, went to the toolshed and donned her pink rubber boots.

“Sarah?” she called a few minutes later, waving me over. Ready for my praise, I obliged. Instead, she handed me a bristled squeegee and bucket, pointed at the rock pool of water and then to the concrete slabs, spilling out several phrases that included the words water, clean, wash, pool. My eyebrows furrowed- that wasn’t on the sheet.

I walked the few steps over to the laminated instructions and pointed, asking the question in as many words as I could summon “But, here. No?”

“Ahhh” she said with some recognition, shook her head and waved a dismissive hand in the universal gesture for “forget it.”

“No” she said, and again handed me the bucket and mop.

I didn’t need translating for this gesture. Clean the pool now.

I said a sad, silent farewell to the laminated sheet I thought would rescue me. So much for my safety raft.

Working in the aviary was like descending into hell.

Specifically, the second layer where stranded, tortured souls yell at every new visitor riding the Death Gondola. (I’m pretty sure that’s the chapter of Inferno when Dante has to clean shit with his bare hands, gets attacked by birds, and absolutely roasted in Spanish for his incompetence, right?) Every bird shrieked every four seconds. Josefina paddled me down the River Styx. I sat in my self-constructed Gondola of Torment.

It was hard to imagine more demeaning work. Each domino of failure fell into one another with a near perfect, chaotic harmony. Josefina would take a quick glance at my cleaning progress and tell me to start over and do it again, or stop me mid-task to ask why I was doing what I was doing (what she had told me to do) instead of something else (that she had not told me to do.) Each task I completed was either not good enough, or 50% wrong, despite my genuine attempts at following her directions.

Take this bucket to scoop up the water in the pool to deep clean the concrete slabs nearby. Wait - stop! That’s too much water from the pool - go get water from the hose instead. Not that hose!

Leftover food goes into the compost bucket. No, not that food - leftover food on those perches goes into a different bucket! Not compost!

The instruction page says to set aside long feathers on the ground to be given to the big cats to play with as enrichment. Josefina says What are you doing? No. Compost the feathers.

Sweep the concrete slabs and the pebbles of the walkway before you deep clean with soap and water. No, not like that. Like this. Sweep away from you. But wait, not on the slabs - on those, you sweep towards you.

Her frustration with me was palpable. It was as if there had been a mandatory orientation class that I’d skipped out of ignorance or confidence. Like I had already been trained for this and should know what she was thinking; how to do each of her secret methods correctly. It was pointless to proactively move onto the next task- even if I took an educated guess, I would probably be wrong. She liked to keep me on my toes, so routine was out the window. Over and over I tried my hardest; over and over I failed her expectations.

My sails were windless. My dignity, trashed. My back, sweaty. The birds: mean.

I’m cleaning up your shit, I thought angrily as they harassed me for the fifth hour straight. I’m literally mopping your shit off the ground and feeding you fresh fruit and giving you clean water. Why are you so mad at me?

It was dawning on me that this aviary assignment might be a game I couldn’t win. Josefina would maybe – probably – never know the extent of my story, my intentions, my work ethic- or how badly I wanted her to think I was good and worthy of her kindness.

And despite everything else I’d found acceptance for- the cold showers, the cockroaches, the nonstop hunger- I did not want to accept that I would do a bad job in the aviary. I did not want to accept that I couldn’t master it, that the birds disliked me, that Josefina thought I was nothing more than a gringo moron.

I could accept being ignored entirely, but I did not want to accept that I was actively disliked and consistently imperfect.

“The birds hate me,” I told Anul at lunch. “And so does Josefina.”

He nodded and looked down at his plate, spearing a bite of fried chicken.

“The birds hate everyone at first,” he said, taking a bite. Chewing, he considered, then swallowed. “And Josefina is like this with everyone. All of the volunteers are the same to her.”

I guess it was a relief to hear that it wasn’t just me, specifically. But I also wanted to be the exception to her rule. I wanted to be different. Not like most girls.

I described the feathered attacks and the bully, Green Parrot. “I’m trying to be calm around them, taking deep breaths and slowing my heart rate - the way I do with other nervous animals.” I had learned this approach when riding horses, training my dog, and befriending the skittish stray cats in my childhood neighborhood. Animals respond best to the parasympathetic nervous system; to rest and digest (instead of fight or flight.)

Another ranger who worked with the monkeys sat next to me, and had been listening in. He didn’t speak English, but cocked his head and looked quizzically at me, then Anul. Anul explained to him we were talking about the birds, aves. He nodded in recognition, then turned back to me and spoke quickly and instructively in Spanish. I glanced at Anul, who was absorbing the directions and preparing to translate.

“He says you should act as if they’re not there. Pretend they don’t exist. To them, you are just a predator. You being there threatens them, so they attack to protect themselves. Better to just pretend they aren’t there, and that they don’t bother you.”

Anul looked at the ranger, then back at me “And” he added in a whisper, “you should do the same with Josefina” he smirked. We laughed.

Okay, so apathy. I’d ignore them.

I knew it worked well with other animals, too. Don’t give them much attention. Go about your business, take deep breaths. Keep your energy to yourself. After all, I thought, I was there to do a job. I was there to work, not be carried away like Snow White and her girl gang of songbirds.

After lunch, I approached the doors of the aviary again, but this time aloof; performing an air of indifference. Acting like there weren’t dinosaur cousins yelling at me, nosediving into my head and shoulders.

What would an indifferent person do? I thought. What would signal that I was completely unafraid?

Four years earlier, after signing the adoption papers, I loaded my new puppy into a crate in the backseat of my car to go home. As soon as the car started, so did he: wailing and crying, howling, yipping- inconsolable. I tried cooing at him, taking deep breaths and long exhales to calm my own body, explaining that we were going home, that it would be okay, that I knew he was probably scared. To no avail. I could sense his panic, and now I was starting to panic, too. What am I doing? Am I making a huge mistake? Is this a warning sign?

After ten minutes, with thirty still to go, I switched approaches. I started singing.

Strangely, this worked. It was as if by doing my own activity- one which required focus and the use of my lungs and ears and body, I had recentered the nervous energy back into myself - back into something I could control. The puppy, my puppy, started to take breaks between his wails. He listened.

I sang Elvis all the way home.

Recalling this unusual remedy, I decided to give it a shot. What came to mind was 9 to 5 by Dolly Parton, and I was buoyed to realize this song was the one thing in the aviary that only I knew how to do. A song Josefina wouldn’t know. An act of secret rebellion, made stronger by its sentiment-

“Want to move ahead but the boss won't seem to let me // I swear sometimes that man is out to get me.”

A little treat, just for me.

I gave it a shot, singing softly and humming the parts I didn’t know, and just like in the car that night, the birds gave me pause. Their animosity wasn’t completely gone, but it was reduced. Replaced with pauses where none existed before, breaks during which their hostility switched to curiosity. They cocked their heads and perched near me for a closer look. They still bugged me, got angry, pecked at me as I cleaned. But the frequency had lowered.

“It’s enough to drive you crazy if you let it”

Singing didn’t solve everything, but it seemed to make the time pass a little faster. It gave my brain a new tune while scrubbing or sweeping or cleaning off the feeding stations- something besides what had scrolled on a loop before “Why do Josefina and these birds hate me so much? Why can’t I figure this out?”

I cleaned up the leftover food from lunch- granola and quinoa spread across the feeding tables- and reached my brush across the table to scrape the grains into the bucket in my other hand. The systems here were frugal in order to be sustainable; what food was left untouched by one animal could be eaten by another, and whenever possible, it was. Leftover granola was set aside for the tapir’s breakfast, or the peccary’s lunch.

A red macaw sat perched just inches away – watching intently while I reached towards the edges of the table, pulling quinoa towards me and the bucket as calmly and indifferently as possible. She leaned towards my hand as it moved in her direction, warning me not to come any closer.

“Working 9 to 5, what a way to make a livin’.”

I avoided giving her attention of any kind. Unlike some other animals, these birds perceived eye contact as a threat, and would start to fluff up their feathers in an attempt to look bigger; the warning sign for an imminent attack. I’d learned this the hard way on Day One.

If I didn’t clean well, I’d have Josefina to answer to. If I cleaned too well, I might get a beak to the fingers, a talon to the forearm. Lose, lose.

“There's a better life-

and you think about it, don't you?”

Every now and then, I’d notice that I had stopped singing. Upon examination, the silence was preceded by unease or fear. I’d clock the pause and wonder why and when I’d stopped, only to remember the sound of swooping wings or alarmed screeching that had initiated the stop. Other times, I’d realize that nothing threatening had happened, but that I’d been swept away in an imaginary worst-case scenario: becoming a pincushion for sharp macaw talons; of contracting the avian flu and having to return to the US; Josefina complaining about me to others- just some weird foreigner singing country music to the birds.

This imagined fear was so familiar I hadn’t even noticed its presence- and I probably wouldn’t have- if I hadn’t been singing and then, suddenly, not singing.

It was nearly impossible to do both simultaneously, so I had to pick one or the other: sing or worry. Realizing this felt important.

Day 3. Picture it.

Screeching littered the clear air. Cages reached towards the sky, tunnels and high-rises of chain-link. Full sun was above the canopy of treetops, reaching a crescendo of heat and humidity that threatened a midday tropical rain. The acerbic scent of birds, mixed with the occasional whiff of lemon-lime dish soap, sitting bubbled in the orange bucket of water. I yanked drooping pants up and around my hips and squatted down – knees wide – towards the stone path. My head regurgitated Josefina’s sideways comment, which she delivered after two solid hours of scrubbing – “un poquito mas.“

A little more.

I had been in the aviary for several days now, yet didn’t feel any more comfortable or close to mastery. Despite telling myself to accept the situation as it was, my lifelong companions- perfectionism, people-pleasing, self-doubt, shame - felt closer than ever.

The sun beat down on my back, intensifying the sweat already soaking through my long-sleeve. I yanked off the gloves, took off my rings and shoved them into a back zippered pocket. I was starting to get blisters from wearing them while scrubbing for so long. I wiped the sheen from my forehead. I sniffed, my nose running from exertion, and grabbed the smooth handle of the brush, gripping it just so, avoiding the cuts and blisters.

At the sound of muffled conversation, my gaze lifted to the front gate clicking open and shut – where a tour group, seemingly a school field trip, entered the aviary along the main walkway. The walkway, I’ll add, that was practically sparkling, having been freshly swept and scrubbed of shit.

Un poquito mas, my ass.

Anul was leading the tour, and when he saw me gave a finger-wiggling wave. He pointed out and named the species of birds and parrots. He explained where they typically live and thrive when not in captivity, how they were some of the most frequently-trafficked and sold animals on the exotic pet black market. He stopped at one red macaw in particular, and in his thick Argentinian accent, told her story.

She was brought to the sanctuary after being found and confiscated by border police. Someone had been attempting to smuggle her across the border; her, and thirteen other chicks. They had been hidden in a garbage bag with no holes.

Out of the fourteen, she was the only one that survived. The other thirteen suffocated around her.

The group of otherwise rowdy teenagers faltered, then teetered towards silence. Anul moved on to other birds - telling equally devastating stories of cruelty that they’d survived before the sanctuary.

“You can see the birds have long talons on their feet, and their beaks are very sharp. Mostly, they use them for finding, gripping, and eating their food - not for protecting themselves.” He turned toward the group now. “If they can’t flock and fly away from danger, they’ll attack with claws. But if the predator hasn’t yet seen them, they’ll go quiet, and sometimes, they’ll confuse and deceive their predators by mimicking sounds of danger“ he said. “They do it in order to hide themselves, to keep themselves safe. Depending on the animal or threat, they’ll make the sounds of their predators - bigger birds, rattlesnakes, jaguars, chainsaws, humans… whatever will scare the threat away.“

Oh no.

I flashed back to the first few minutes I spent waiting outside the aviary, the “hola’s” I had cheerfully lobbed back at my new colorful friends.

Now I realized what I had done. I had confirmed their suspicions immediately.

I was a predator to be feared.

Anul finished his spiel, then took the group to the next area. I wrestled with what I’d learned.

I didn’t speak the language of birds. There was no clear way to communicate my intentions to them – to give them a clear message now, after the fact, that said “My bad! I’m just here to help, I mean you no harm! You can trust me!”

Nothing like that would be possible. There was nothing I could do to rectify this situation. This was yet another strange kind of surrender for a controlling, people-pleasing, perfectionist keen on Being Good. I would continue to show up here for eight hours a day and the birds would continue to assume me a threat – squawking “hola “ to goad me– speaking in tongues of self protection. I would not be able to disprove them. I would not make them love me. I would not become Snow White and they would not carry me away.

It’s a smart tactic to copy your predators.

It’s strategic to mimic danger to- counterintuitively- escape it.

Mimicking our predators allows us to camouflage and disappear into the periphery, to become not yourself, not weak or vulnerable. Instead, you can play something strong and unafraid – another one of the powerful. By becoming the predator, you can opt out of being prey.

Macaws are intelligent, deeply so. Their complex cognitive abilities rival human toddlers. They live within complex social units of 10 to 30 peers. The section of their brains (spiriform nucleus) devoted to intricate communication, problem-solving, and fine motor skills is roughly 2 - 5 times larger than other birds, like chickens. In fact, it more closely resembles the brain of a primate, like a monkey or human (1). This part of the brain is thought to play a major role in the planning and execution of advanced behaviors (2).

Macaws have their physical protections, should they really need them. But I’m sure you can understand the advantage of using more advanced technologies, more efficient weapons – mimicking, tricking, pretending to be something they are not. Repeating the sounds of harm they’ve been subjected to. Scaring away others the same way they have been scared.

A few months prior to my trip, I had posted a piece about my love life; about dating in an attempt to find my Dream Man. It was a combination of years of painful experiences and stories, something I’d written and edited for months, a sentiment I’d worked through extensively. I knew it could ruffle some feathers, but it was true and honest and vulnerable and I wanted to share it. I was proud of it. Despite knowing this, I was not prepared for the response I received from people I’d never met.

The comments, replies and DM’s I got (before I stopped reading them entirely) stayed with me.

“I don’t feel bad for her.“

“Just wondering, but what exactly do you bring to the table?“

“Have you ever considered that you’re the problem?“

At first when these sentiments circulated in my head, it was clear that they were foreign and not my own. When they appeared, they were spoken in the voice of Other. (And specifically, a male voice. Because all of the comments came from men.)

But over time, they warped. After a few days and weeks, they were no longer the distant, cryptic voice of the anonymous internet, but a voice more familiar. My own.

I don’t deserve sympathy.

What exactly do I bring to the table?

I’m the problem.

I could no longer distinguish which harmful thoughts were my own.

I was confused. I retreated away.

The birds in my head had learned to mimic their predators to stay safe, and it worked.

If I sound like a predator, I won’t become prey.

The instinct to adopt others’ venom is shared between humans and macaws. We threaten others with the precise kind of poison that has hurt us. We use our advanced intelligence to mask our vulnerability with familiar sounds, with borrowed weapons.

We use this tactic on others. We use this tactic on ourselves.

The aviary delivered me to my personal hell. Tiring work I could never master. People I could never please. Birds like physical manifestations of the tormentors in my skull- nonstop voices I had long since forgotten, were not mine, did not speak truth. Logically, I recognized their lack of authority. But they were loud all the same.

In the worst times of our lives, we find ourselves stuck in an aviary. All we can hear are the cruel thoughts we’ve grown accustomed to. The meanest of accusations, the loudest and most cutting characterizations, most memorable of venom used against us. Now, spoken in realistic, familiar voices. Adopted then used by ourselves, against ourselves.

During my actual aviary stay, the voices were loud and relentless.

First, topical.

“You’re not doing it right. She’ll be here any second to scold you.”

“How hard is it to figure out how to clean? Aren’t you smarter than this?”

“Why do you want her approval so badly, anyways?”

Then, broad and sweeping.

“You’re not strong enough for this experience. Quit while you’re ahead.”

“You’ve made a huge mistake. One you can’t fix.“

“Your life will never be on track, and it never has been.“

“You should’ve just stayed put in Colorado, gotten a new job, worked harder, started an Instagram account for your writing or given up on it already. This trip will derail your career, if it doesn’t kill you first. You’ll end up broke. You should be like everyone else - bored and working toward some suburb and an SUV. Why do you think you could have more, could have different? What makes you think you deserve it?“

There are two kinds of acceptance for venomous thoughts, and the distinction is vital.

There is acceptance like a college admission; a welcoming and integration of an outsider into your ivory towers. That is to say, there is acceptance of these thoughts as correct.

And there is the acceptance that they exist, period. That doubts and fears within our internal narrative may never be eradicated completely.

This second option does not require that we give these thoughts credibility. It does not mean endorsement. Instead, it simply means that we recognize our inclination to keep ourselves safe by mimicking our predators. We recognize this inclination in others, when they use it against us.

After all, just because a macaw sounds like a jaguar does not mean that it is one.

I had tried to approach the thoughts in my head the same way I had approached Josefina and the birds. First, I tried to prove them wrong. Then, I pretended they didn’t exist.

But they did exist.

Just like the doubts and venomous accusations I had adopted, mimicked, or created from scratch- they existed. Regardless of whether I fought with them or pretended they weren’t there, they were still present. Fighting them at each turn was exhausting. Pretending they weren’t there only made them louder. Both options were laborious.

So in the final hours of my time there, I switched to a third and final approach. The approach of giving each of our experiences and realities equal amounts of space and credibility: mine, Josefina’s, the birds’. I wouldn’t be here forever, but for now- these birds were my roommates, my neighbors. Fighting them or pretending they didn’t exist wouldn’t make time pass any faster - it would only exhaust me.

It was the kind of acceptance that was really more like surrender. These shrieks, like the comments in my head, would continue forever; the birds would never understand that I didn’t want to hurt them; they and Josefina would never be kind to me; I would always be the bad guy in their stories.

And!

I had worked hard; I had chosen kindness even when it wasn’t returned to me; I made real attempts to make this space cleaner, better; I made mistakes and corrected them; I wanted to do good work. That was true, too.

I’d probably always feel some twinge of unlovability, of loneliness, of unworthiness. That was part of working in the aviary. Maybe if I had been there longer, I could have gotten closer to something like compassion - for the birds, for myself.

At 6pm and the end of my final shift, I gathered my tools and brought them to the toolshed. Filled up twelve jugs of water to be used for the next day’s water refill. Swept up the feathers on the concrete and into the compost bucket. Peeled off the rubber gloves - now with cuts from the chain-link spikes - and washed my hands. Grabbed my water bottle and said goodbye to Josefina.

I walked through the gate and shoved it closed, hearing it click into locked position. The birds kept squawking. Safely out of the splash zone, I took off my hat and shook out my hair - ready to end my night with a walk along the river with Ralph.

I hadn’t gotten what I’d hoped for in the aviary, but I did get something useful. A fresh metaphor for torture. A place to return to when I found myself overtaken by the sound of predators.

Next Up: Chapter 5

Sources:

Parrots have evolved a primate-like telencephalic-midbrain-cerebellar circuit, Nature (2018)

The 5 Smartest Birds You Can Keep as Pets, The Spruce Pets (2021)

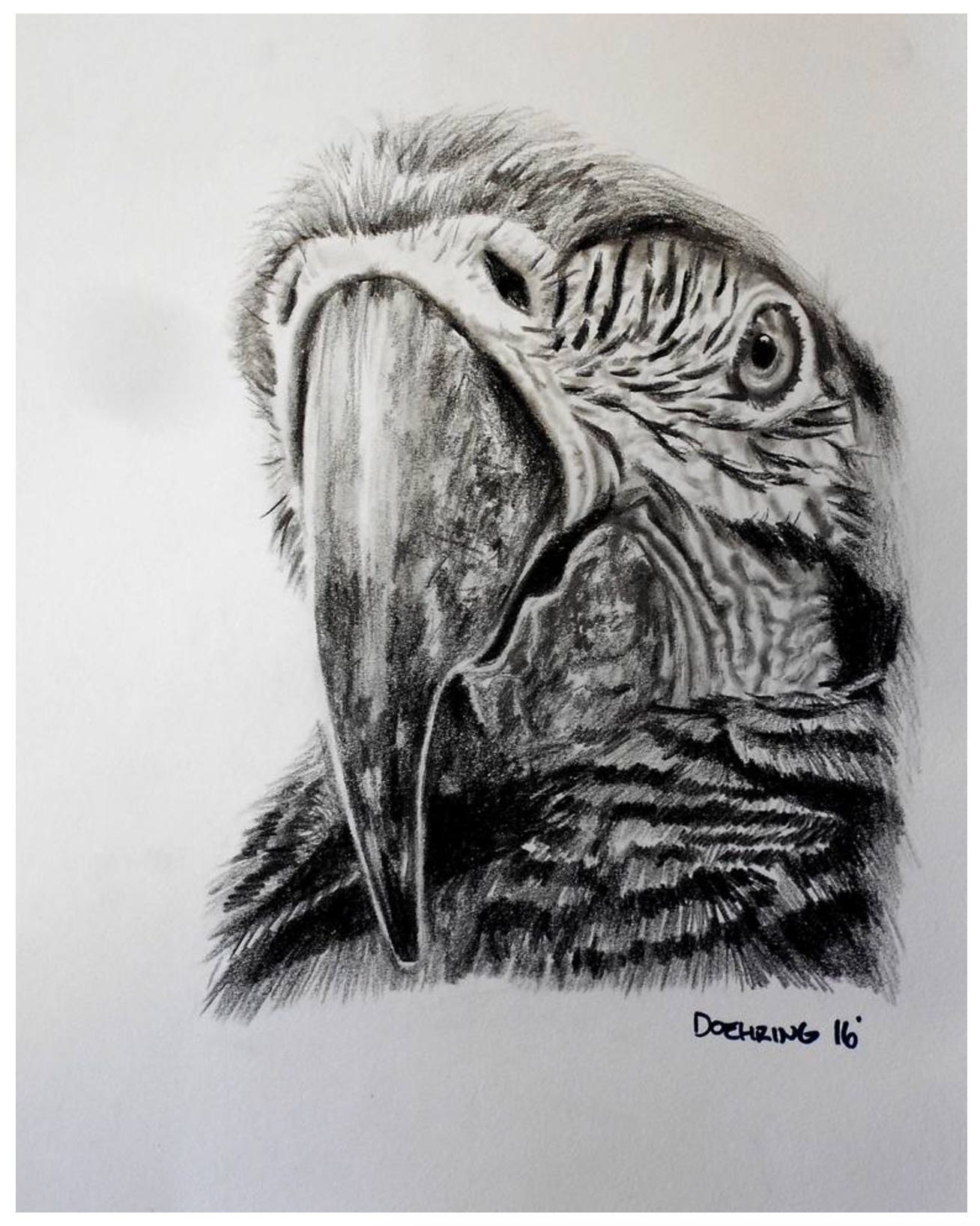

Artwork by Jennifer Doehring “Macaw Drawing’. See Jennifer’s work here