Reminders for Humans is a monthly series that explores a natural phenomena, and how I’m applying its wisdom to my own human life. I’m a scientist by training, and a gushy poet by nature. Expect both.

This is Chapter 7 of 10 of an ongoing series about my time volunteering at a wildlife sanctuary in Bolivia. Read Chapter 6 here. Special thanks to ’s wonderful class (Writing The More than Human World) for helping me to tell this story.

Reminders for Humans:

Social primates, like spider monkeys and human beings, rely on deep, complex bonds with their peers to survive. They are in near-constant contact with one another. Touch is indispensable.

The early years of life are critical for a social primate to bond with its mother. A baby spider monkey needs at least two years of constant contact to be well-adjusted for life as an adult.

The three components of self-compassion are: self-kindness instead of self-judgement; common humanity instead of isolation; and mindfulness instead of over-identification.

She was born to some mother, no doubt just as hairy, somewhere in this forest. Eight months ago. And I bet she was held, loved, ferociously.

Sergio says the poaching business has been steady and strong, a regular heartbeat, for generations - so it’s hard to say if there was a sudden uptick, a high demand on the day it took that hairy mother from her.

It was the end of autumn when she was born, and by winter she was alone. 2024 was a year most internet liberals couldn’t fathom overlapping with words like spider monkey bushmeat. Most internet liberals don’t live in Bolivia.

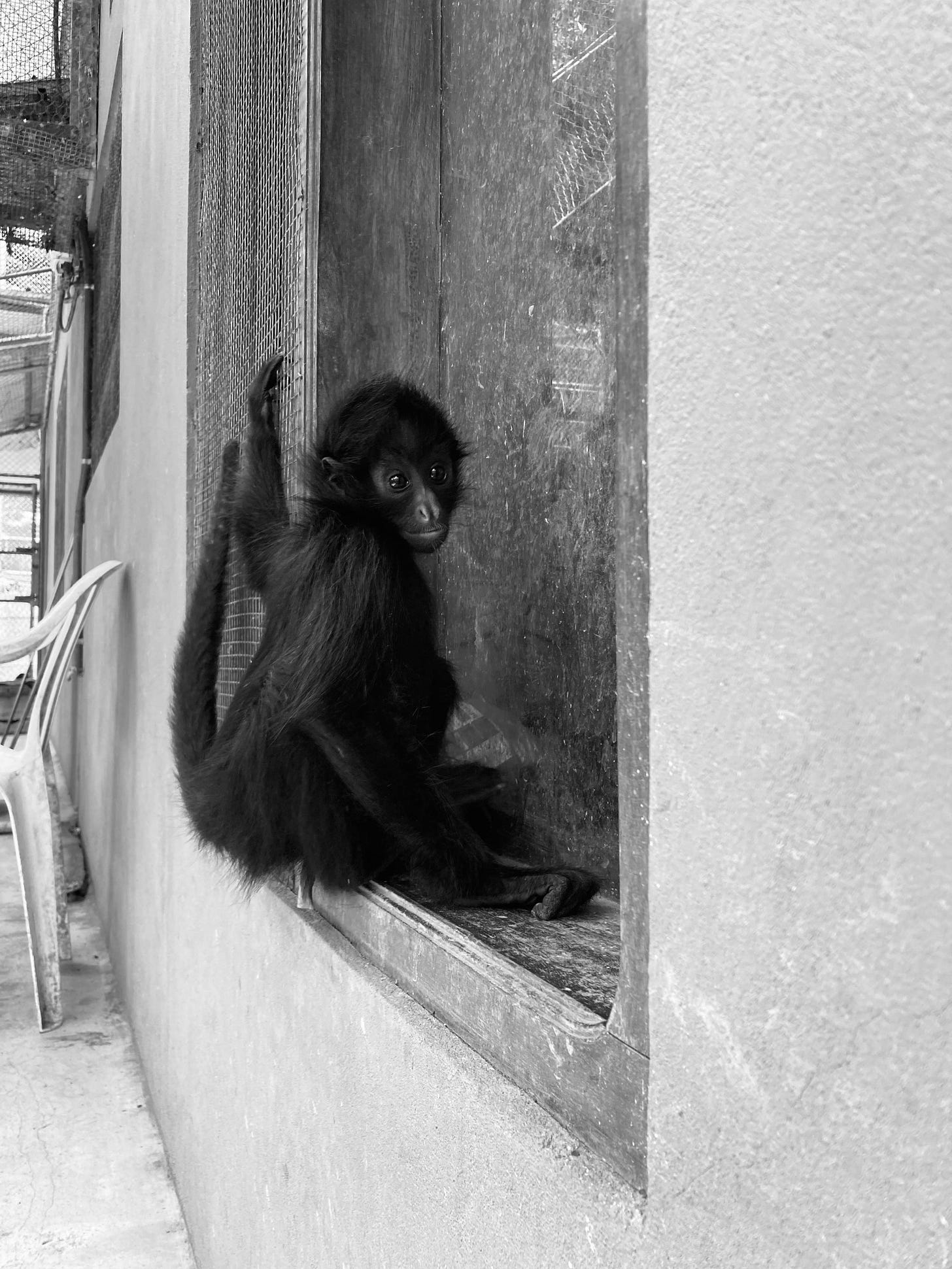

Chioma means God’s Love - a name the staff chose upon her arrival. They meant well. They didn’t yet realize her lineage was that of warriors.

Breakfast was rice porridge with a cinnamon stick, which broke apart in brown flakes swimming in mush. I took long sips of black instant coffee and disappeared into the background of Spanish chatter around me.

“Sarah?” the volunteer coordinator called from the other end of the table, breaking my spell. I looked up.

“I’m changing your area today from rewilding. We need help with the baby monkeys.” She used the meat of her fist to erase my name from Rehabilitación, then scribbled it with two dates in the empty box under Mamá mono.

“Okay, gracias.”

“Ahhhh, it’s your turn now!” Heidi elbowed me playfully. “Good luck-” she raised her cup of tea in salute, her eyebrows high over wide eyes and shook her head, then returned to her porridge. “She is a full time job. Make sure you wear a hat.”

Heidi was another volunteer - a woman in her sixties, married with two adult sons, who was taking a break between jobs where she lived in the mountain town of Santa Cruz, a few hours away. She’d arrived a few days before, fresh off an intensive hiking and meditation retreat in India. I watched her flip through pictures of her bathing in the Ganges, her grey hair flowing downstream. She’d always wanted to lay in its holy water.

“I love my husband, but he doesn’t like these travel adventures like I do-” she said on the day we met, while we chopped vegetables and fruits in the prep room. “He doesn’t need to do them. But I do. So if he doesn’t want to come with me, I go alone.” She grinned, “And then I come home and tell him everything.” She scooped chunks of papaya between palms and dropped them into the red bowl to her right, wiping her hands on the tan volunteer shirt, then looking up at me through purple glasses. “It works for us.”

Heidi is the kind of person you meet, if you’re lucky, in the midst of an adventure. Who lives on average halfway outside of her comfort zone, which means you’d probably only meet her if you were doing the same. And I was delighted at my luck that our adventure-schedule overlapped.

“So what should I be expecting?” I asked between bites. “Why the hat?”

“Oh - “ she chuckled, putting her spoon down. “She will climb — ” she pantomimed ladder rungs, “onto your head. And when she wants to get down —” her hands pulled downwards as if grasping ropes, “she will use your hair.” Her nose wrinkled into a grimace.

Awesome.

“She is quite cute though,” she admitted. “Running around with her little blanket, like Lean-us.”

I cocked my head, confused.

“You know, the Peanut? The boy and his blanket?”

I laughed. Leanus. Linus. Same difference.

Despite the warnings, I was bubbling with excitement. Who doesn’t want to hang out with a baby monkey?

I would learn by lunchtime that this rhetorical question had an answer: any sane person.

I followed a path I’d never been down before, passing through clanking gates, crossing over the river and climbing up and up the side of the ridge. After five minutes in the still-cool of morning, a building appeared on my left, tucked behind a final gate. When I creaked it open, a head popped out from the open door to the kitchen. It was Erika, one of the three other women who shared the bedroom bungalow in Ralph’s House with me. She didn’t speak English, but was learning. A few times I’d come into the bedroom while she was mid-lesson, and would hear her quietly practice phrases, “she… go-ess… to the.. doct-ore.”

She greeted me briefly, her hands preoccupied with food chopping, and nodded her head to the right— around the corner of the house.

On the other side of the building was a fenced courtyard. A grey-haired man stood with his back to me, a baseball cap on his head and a baby monkey perched on his neck. Her legs folded beneath her, hands on his head, and a long black tail hooked around him like a necklace. They stood watching the adult monkeys on the other side of the chain-link. I could hear him speaking softly to them, or to her, or both.

I said hello. Their heads turned toward me in synchrony.

“Hello!” he said, moving toward me.

“I am Sergio. This is Chioma.”

He said it slowly, Choyyyy-muh. His eyes were soft, a grey-brown. He turned to look at her on his shoulder.

She watched me intently.

"Hi, Chioma,” I cooed. “How old is she?”

“Eight months,” he said with a heavy accent, looking down to orient himself and lowering down to a criss-cross seat on the concrete. I joined him. Chioma abandoned his shoulder and jumped to the ground.

She looked like the baby Grinch. Covered with thick, wiry black hair that stuck straight up like a mohawk on her head. Laughably long limbs, a squished pink face and black eyes. She walked on all fours, her long tail raised like a periscope. She started to examine me. Manually. Biting the white rubber of my beat-up converse, then climbing on my lap to test the various fabrics I was clothed in, then losing interest. She clambered off me and towards a red rope that hung like a clothesline in the pocket of the fence corner. She jumped onto it effortlessly, hanging from it with a hand and a tail, swinging erratically. Bored, she dropped to the ground and turned the corner toward the kitchen. I faintly heard Erika’s voice greeting her new visitor.

“She came to us when she was aboooouut three months old,” Sergio estimated, “just a tiny thing.” He held his hands around an invisible softball. “Normally, the babies stay with their mothers for three years, with her at all times -” he took off the cap and scratched his thinning hair, then fit it back on. “They need three years of constant contact.” He emphasized each word. “We can’t just introduce her to the females of the troop here, sadly - they almost never care for a baby they don’t know.” He gestured toward the adult monkeys lounging on the other side of the fence. “Sometimes, they will kill an outsider. So until she is old enough to be familiar and hopefully accepted by the matriarch, she lives with us. With my wife and I. Every minute of the day—“ he paused, “and night.”

There were deep wrinkles on his forehead, grey in his stubble. This wasn’t his first rodeo. Another volunteer had told me Chioma was the tenth baby they’d taken in thirty years.

“Wow.” I mused, shaking my head. “So that’s where I come in?” I asked half-joking.

He laughed. “Yes, exactly. You are here to give me a break. So I can get some work done.”

With that, he stood up, looking toward the corner Chioma had disappeared around. “She is very, very bonded to me,” he said quietly, “so I am going to try to sneak away while she’s not looking. Otherwise, she’ll do anything to stay with me.” He handed me a grey microfiber blanket. “Here— you’ll need this.”

I clutched it and got to my feet. He slunk quietly and quickly to another door at the end of the walkway.

I waved. “See you in eight hours!”

The door closed with a click.

The black-faced spider monkey, also called the Peruvian Spider Monkey, has a natural range throughout Central South America in the southern Amazon Basin: particularly, Peru, Bolivia, and Brazil. The species is generally considered Endangered- estimates show that their total population has declined by at least 50% in the last 45 years.

“This species is hunted locally for meat and hunting remains one of its biggest threats. Habitat loss is also a major threat; huge amounts of deforestation for cattle farming, agriculture, mining, and logging has resulted in severe habitat loss across this species’ range. Planned highways across the southern part of their range adds yet another threat to this species’ survival by threatening habitat and also opening up the area to further hunting.”

The entire troop varies in size - but can contain up to 40 members. Though, like other social animals, they exhibit a fission-fusion social system, “which means that members of the same group often split up into much smaller subgroups, often just 2–4 individuals. The whole group is rarely seen together and the only stable grouping is that of a mother and her infant.” 1

Babysitting a baby monkey is a little like babysitting a toddler, if that toddler could move effortlessly in all three dimensions, takes zero naps, and bites you.

It’s similar in the main responsibility: follow a stumbling yet extremely fragile and valuable infant around while proactively removing potentially dangerous obstacles. And by how utterly exhausting this is. Each hour ticks by like molasses. Every four minutes is an adventure of its own. There are only so many adrenaline crashes one can handle in an eight-hour day, spiked up and down every time said baby monkey almost escapes through the fence, jumps onto a kitchen counter littered with knives, and uses your hair like Gymnastics Rings.

Twelve minutes in, I decided I far preferred the physical exhaustion of carting buckets of food and water into the forest to the mental exhaustion of repeatedly wondering what the fuck is she about to do? and finding out. Chioma was in nonstop motion, no downtime. And the obstacle she most enjoyed challenging herself with was my body.

She’d loop her tail over my wrist while I stood, pull herself up by my shirt with another arm, sit on my shoulder long enough to catch her balance then leap to the rope three feet away. Then, pendulum-swinging back and forth for momentum, launch herself back onto me - grabbing fistfuls of whatever she could to steady herself; hair and fabric and skin.

I’d lift an arm parallel with the ground, and she’d grab on to lower herself to the concrete. Then clamber to the next surface from which she could jump onto me from. Again. And again. Ad infinitum. For eight hours.

It felt a little like being on a giant air hockey table and trying to sidestep the speeding puck. Whizzing, always, with sheer energetic volatility. Eventually, you’d get tired of running and just let it slam into you every now and then.

On Erika’s counsel, I tried to take her for a walk. This required getting her swaddled in her blanket and carrying her around the sanctuary grounds for a stroll. The monkey moms did this occasionally to acquaint the babies with the surrounding jungle. If she still had her real mom, she would have already seen every corner of this place, from the best seat in the house: clung to her underbelly.

The key word here is tried.

I’d get to the fence with her in my arms, airing a calm swift precision. Each time I stepped over the threshold, she leapt out of my arms and back to the courtyard.

No dice.

It’s nearly impossible to control a baby monkey in any meaningful way. I don’t mean control like, control. But you can outsmart a human baby. You can bribe it with snacks and television, or strap it into a stroller and go for a spin. Hell, you can put a diaper on it- something this free-shitting monkey would rip apart in seconds. Babies are easy to trick. It’s an evolutionary blessing I didn’t recognize the value of.

You can’t trick a monkey.

You can’t read it a story. You can’t play with blocks. You can’t lie and say the Tooth Fairy told you she will only come if they go to sleep right now and don’t get up until their mom comes home. You can’t feed it goldfish and applesauce so it crashes for twenty blessed minutes. Chioma wasn’t even hungry. That’s how bad it was.

And you certainly can’t pick it up and move it anywhere.

I learned this the hard way, of course. You can’t just pick up a monkey like it’s a baby, or a puppy, or a cat, or any other animal I’ve ever picked up for that matter. This is because a spider monkey has the intelligence of a human without the fear of God. It has superhuman strength and, effectively, five arms. Go ahead and pick it up like a baby. Try. It will untangle itself from your grip with one hand, grab your hair with another, bite you, and strangle you with its tail. And still have two hands free to flip you off.

You cannot make a monkey do anything. You can simply suggest options.

Perhaps you would like to take a bite of banana? Possibly are you interested in holding onto my hand so I can elevator lift you up to the fence? What about a quick sit in your grey blanket? How about not biting my legs through my clothing? How about stop pulling my hair out? How does that sound?

By the time I saw Heidi again at lunch, I looked like a grizzled war veteran. The light gone from my eyes. The butterflies in my stomach squashed to colorful pulp.

“How was it?” she asked.

“Jesus.” I said, not knowing where to start. “She’s…. a lot.”

“Yeah.” She said. “They wanted me to be there with her for eight days,” she said in a low voice, eyes wide. “I said, I cannot do it.”

“Oh, my God. Absolutely not.” I unbuttoned the tan long-sleeve and hung it around the back of my chair.

“Oooo,” Heidi peered behind me, pointing to the fabric. I looked. There was poop speckled on the back. How I’d missed this was unclear. “She did this on my clothes too. All of them, dirty, dirty, dirty.”

I picked it off the chair, gingerly folded it together, and put it on the ground.

“You need a new shirt,” she said. “The woman in the laundry room will give you a clean one, buuuuut-” she pursed her lips, “she’s only there on Thursdays.”

It was Friday.

I rubbed the heel of my hands into my temples. “Welp. I guess I’ll wash it in the sink after lunch.”

Heidi hummed in agreement, and started cutting her chicken and yucca fries.

When I was a kid, one of the roughly fourteen-hundred stuffed animals I owned was a monkey with egregiously long arms. The hands stuck together with two loud velcro pads. I kept it looped around a post of my bed frame, and sometimes when I needed a buddy, I fashioned it around my neck. Hanging off of me like a backpack.

I’ve written about this before, but decades later, in throes of depression, I returned to that monkey. Not in its physical form- which had been lost when the house was sold or possibly before. But in a moment of sheer desperation, likely inspired by my therapist's ongoing prescription for self-compassion, it was conjured back to my present.

In that moment, the ache in my throat which was never far away switched from a mysterious invisible curse— You’ll never be without this pain. You will never heal. You will never be whole — to something physical. To a velcro monkey. To a buddy.

Dealing with your shit is a lot like having a second job. … These days at this second job that I never wanted, of teaching myself that I am lovable, my main task is imagining that there is a small monkey sitting on my hip.

She is just a little chimp, with furry arms and human-like hands and giant shining eyes and God Damnit she is so cute, but holding her all day long can be exhausting. Sometimes I forget she’s on me until I start to feel strangled by the flavor of unnamable sadness that I’ve found myself in. She is so desperate for love that she would climb all over me in an attempt to get my attention, my two eyeballs to look into hers and somehow say in a shared language, yes you and I are on the same planet right now. She is holding on for dear life to someone solid, with hands clasped around my neck, and this is why I feel strangled by how lonely and unloved I feel sometimes. Her tiny human-like hands are clasped right where the decades-long lump in my throat lives.

Most days I forget this whole exercise until I am being very Mean to myself. And when I realize this meanie has taken over, I try to trace back the scars that the whole ten to eighteen to twenty seven years made inside of me. Trace their pink lines without wincing.

I remember my chimp and look into her two eyeballs and hold her so close and tight and say I know baby. I know. I’m so sorry.

Dr. Kristin Neff (the mother of modern self-compassion) describes it like this:

“Self-compassion simply … means being supportive when you’re facing a life challenge, feel inadequate, or make a mistake. Instead of just ignoring your pain with a “stiff upper lip” mentality or getting carried away by your negative thoughts and emotions, you stop to tell yourself “this is really difficult right now,” how can I comfort and care for myself in this moment?”2

To this day, I’m not sure why it felt so much easier to accept the needs of a small furry chimp than my own. To care for her. To find compassion and kindness for her grief, when these phrases never became actions when directed towards myself.

I don’t think I could entirely excavate the complexities of that if I tried. Years later, the why is less important.

What’s more important was the imagery. Suddenly, now disembodies from me and placed into the frame of a furry rugrat, I could feel how sad I was for her. I could feel how unjust it was, what she had endured. That she had deserved better. And mostly - how those little eyes were not asking for me to rectify past wrongs, but instead, were simply asking for my presence. Were asking to be seen, in all of her loss, without looking away.

In the year or two since I’d first been visited by this imaginary monkey, her visits had become increasingly less frequent.

At the beginning and in the worst of it, she was on me from morning to night, day after day, strangling me, asking and asking Do you see me? Needing constant reassurance. Needing constant holding, nurture. And as the days and weeks passed and I answered her again and again, she seemed to trust me more, trust that she would not be forgotten, would not be abandoned again.

Over time, the debilitating lump in my throat was weekly, then monthly, then sporadic.

Chioma, of course, subconsciously represented the opportunity to actually experience that image. But she was doing a shit job of acting her part.

On day two of babymonkeysitting, I attempted to fix my attitude. To show up with calm confidence, even enthusiasm, for another eight hours together, despite the abysmal chances it would be any better than the day before. And if it wasn’t, at least I could say I kept my side of the street clean.

And wouldn’t you know it, day two was the same as day one.

It was a terror, really, to be in her vicinity - due to the immense amount of physical damage and pain to endure. I already had little pockmarks across my arms and legs, around my neck, between my fingers from her razor teeth. Eventually, I said fuck it with the hat - she pulled it off anyway. I let my hair down in all its length, despite the potential (definite) feces that would be in it by the end of the shift and the chunks I’d leave behind in my wake. If she was going climb my hair regardless, I might as well unhook the ladder.

All she had going for her was how goddamned cute she was.

There were glimmers. We did have some adorable moments together. Moments. Not minutes.

These are what you see online in videos of people who have purchased baby monkeys as pets, which sadly convinces others to do the same. (Let me be clear that this is not only problematic, but also a terrible idea if you are interested in maintaining any form of sanity. The cute moments make up roughly 0.01% of all moments.)

But they did exist.

Like when her clammy tail would wrap around me as she walked by. Almost like a friend placing a hand on my shoulder as they passed.

People talk about how spider monkeys’ tails are like a fifth arm, a prehensile appendage, and this is not just because it is strong- but because the underside of their tail has the same smooth flesh as the palms of their hands and feet. You probably wouldn’t know that unless you got up close and personal with one. I certainly didn’t. Despite its appearance, it’s not all furry - it’s got just as much strength and grip as one of their hands.

Pushing her as she swung on the rope. Being her Home Base when she was startled by an adult male moving quickly a foot away. Holding the grey blanket out to catch her as she leapt from the fence into my arms. Offering a finger for her to grab enthusiastically with her own. Grooming the fur on her back while she sat near me, copying the timing and technique of the adults on the other side of the fence.

Nothing I did managed to satiate her for very long, but there were a few tricks that calmed her when she was close to my head and in a particularly toothy mood.

I’d imitate the adult monkeys, cooing at her with a throaty yet quiet sound like, uh-uh-uh-uh-uh. Similar to the famously monkey noises ooo-oo-ooo, ah-ah-ah - but quiet and quick, guttural, solely in the throat. She would say it back.

And there was this: if she was in my lap, minimally raucous, I would blow a thin cool stream of air on the top of her head. Like a biological cheat code, immediately her face would soften and calm, her eyes close, her tiny head tilt back. Something about the air, or the temperature, or the feeling of it made her Buddha-like. Her lips would part, her eyes flutter. For a moment, she was in total surrender. Bliss, maybe.

Our last day together was just like the others. I followed her around with a hand extended. She climbed me. We watched the adult monkeys on the other side of the fence.

The staff all seemed to be able to recognize different monkeys on sight. I attribute this to their daily closeness with them- and that many of the workers had been there for years; had seen the monkeys age from Chioma’s size to adulthood, and watched them eventually find their place in the troop. I couldn’t tell one from the other. They all looked the same to my untrained eye.

But I’d been told about Nina. And that day, while Chioma and I played with another piece of foliage she’d unearthed, I noticed rhythmic clinking of a fence being traversed and a shadow to my left.

“Holaaaaa, Ninaaaaa” Erika called from the kitchen.

I looked over. Nina hung on the other side of the chain link, dangling comfortably from one long, outstretched arm above; her feet and tail resting lightly into silver diamonds below. I hadn’t been this close to an adult since Carlos and I had been attacked by two males in the jungle a few days before.

I approached her calmly. Her head was just higher than my own. Standing up straight, she probably would’ve been close to my height.

The monkey ahead of all the other females in social rank and group devotion, Nina was the alpha female in a matriarchy. I always suspect the alpha must be domineering and ruthless. But I never saw that from her.

She stared beyond me with soft eyes. I put two fingers through the fence. An invitation. She looked down to consider me, then worked her free hand through a diamond. If a human hand is a square, a spider monkey’s is a rectangle. Their fingers seem to never end.

She rested it there for me, hand outstretched and relaxed. Laid it out like an offering. Charcoal black skin. Never-ending fingers. Delicate muscles wrapped in smooth callouses bumping from knuckle to knuckle. She returned her gaze to the canopy.

I took the offering.

I placed my left hand gently underneath, stroked the smooth pads of her palm with my right. Fit our hands together and held them like that, holding my breath. Then resuming it, remembering its ability to stiffen me and thus, startle her. I didn’t want it to end. I pushed out stale air through my nostrils.

We made no eye contact, but to hold a monkey’s soft, warm hand in yours is something beyond intimate. Feels like being given a gift. Feels like butterflies in your stomach. Feels like, how on Earth am I alive for this?

Insects droned and chirped, the heat of the day blared through the leaves, the scent of wet jungle everywhere while we held the simplest of connections for heartbeats and heartbeats; inhales and exhales. All the while, emptying myself of everything, everything, everything. Making room for this moment to absorb into me permanently, totally. I wanted to be taken by it like a prisoner.

Nothing else mattered, not Chioma, not how bad I was at this job, not the concoction of emotions I was otherwise swimming in after JT and Carlos and the donkey and osos y felinos and the life I left back in Denver.

Only Nina.

She knew I had nothing to give her. Her palm wasn’t outstretched in anticipation. It didn’t seem to be outstretched with any flavor of intention, really. But something much softer. Something I struggle to name accurately. Though, what makes me think I could?

After a time, she folded her fingers in and retracted her palm just as gently, then continued along. Back to the trees, back to the canopy. Back to being whatever an alpha female entails.

I would like to be led by her, I thought.

I was pushing Chioma back and forth on the rope when Sergio popped out of the door, slinking quickly to the back of the building to avoid being seen.

In a millisecond, I remembered my job to preserve his alone time, and reacted instantly, grabbing for Chioma under her armpits. It was too late. She had seen him, and was in her own instantaneous reaction: That’s my Dad.

What followed were about five seconds of struggle, where I (unsuccessfully) tried to keep her from leaping towards her favorite person in the world. It ended when she sank razor-sharp teeth into the meat under my left eye, then my cheek. I released her abruptly, hot rage coursing through my chest, and she scurried towards him. I held my face to quell the sting and looked over.

Chioma perched on his shoulders, identical to our first meeting. He looked at me apologetically, shrugged his shoulders, and said, “It’s okay - I’ll take her. You can head back a little early.”

I was entirely pissed and now hot with adrenaline, but relieved by my sudden freedom. I nodded and said thank you.

“No-” he countered quickly, “thank you. She is tough to handle.”

Understatement of the year.

I waved and they turned back. I went to the kitchen, grabbed my water bottle and checked the damage in a faded magnetic mirror on the fridge. She’d broken skin in a few spots, and it was already puffy. I never thought my first black eye would be from a four-pound monkey. Put it on my tab, I guess.

Erika came in behind me. “Hola, Sarah—”

I turned around. Her brows furrowed together then apart, in confusion then recognition. “No, Chioma?” she winced. I nodded.

She pointed to a red scab on her cheek. “And, me.”

We high-fived.

Spider monkeys, like humans, are social primates. They interact with the world through their connections with each other. They experience themselves through the eyes of their social bonds. A spider monkey stays with its mother constantly for nearly 3.5 years.3 The first 2 - 3 years of constant contact are nonnegotiable for rehabilitation centers like this one. Without that time, the babies will simply not survive as adults. They will not be well-adjusted for their environment. They need touch, connection, two eyeballs that say yes, you and I are on the same planet right now or else they will die. It’s not needy. It’s just a fact.

(Which, of course, leads me to wonder what that means for human babies.)

“Among foraging, locomoting, reproducing, and sleeping, grooming completes this group of indispensable functions upheld throughout primate societies. Where grooming oneself operates with a hygienic purpose, cleansing debris and parasites from the pelage, social grooming is performed primarily to enforce and maintain relations among the group. After a conflict or dispute, for instance, grooming is often implemented for the purposes of resolution and reconciliation. This is the language articulated throughout primate societies for the expression – “I am sorry, please forgive me.” Mothers can be seen grooming children. Friends finding solace in grooming one another. Subordinate males seeking refuge through grooming the alpha. Social grooming is an adaptable action that can communicate an assortment of messages.” …

“… Gestures of reassurance, oftentimes through physical contact, perform a significant role in abating conflict and hastening its resolution. During, or after a conflict, members of the group often touch the concerned member, a sign of support.”4

I can’t tell you the number of times I watched two monkeys sitting next to each other, watching the world, touching arms. Taking turns grooming each other in long, considered, gentle strokes.

Once, I watched as a female lay on her belly in the shade of a tree- her legs behind her and her arms above her, Superman style. Another walked over and laid down in the same position to her right. Then lifted and placed its arm over hers. They lay there like that for five minutes.

They need each other in order to survive. Most mammals don’t need each other like that, but spider monkeys do. Social primates do. Humans do.

How could I be mad at Chioma for how desperately she needed her father?

Couldn’t I understand that, too?

Wouldn’t I have attacked anyone who got in my way, just so I could be near him? And when I couldn’t, wouldn’t I have punished every poor, well-meaning bastard who crossed my path?

Hadn’t I?

Chioma didn’t play the role of velcro monkey that I’d cast her into: conciliatory, meek, sad, victimized. She was a warrior. Six months ago she’d been ripped from her mother, who was possibly killed in front of her, so she could be sold on the exotic pet trade. She had lost everything. Because of course, the only currency that matters to a social primate is connection.

How does a small thing hold so much devastation in her tiny body, and not become a force of nature? Not bite some motherfuckers in the face every now and then?

I left the area that day, tromped back down the path to Ralph’s house, and for days pouted and bemoaned to Heidi how Chioma’s was my least favorite area so far. Because she didn’t play along how I wanted, I didn’t play along either.

I expected her pain to manifest differently.

A baby monkey, forever scarred and brutalized by members of my species, was not grieving the right way for me.

But that’s not how compassion works. That’s not how it’s supposed to work.

If our self-compassion is only activated when we fit into the characteristics we’ve determined to be deserving, it is not self-compassion. This is like calling strings-attached love unconditional. It’s not. If I must earn compassion from myself, it’s not compassion: it’s judgement. It’s self-flagellation.

Self-compassion is this: I see what you’re holding. It looks heavy. I’m sorry.

Self-compassion is: Not every day has to be a good one. You don’t have to be perfect to accept care and kindness.

Guess who I don’t feel super compelled to give my kindness and compassion to? Someone who bites me in the face.

Guess how I often treated people in the throes of my depression? Metaphorically biting them in the face.

And for the final round, guess when I struggle the most to give myself any kind of compassion? You guessed it! When I have metaphorically chomped down on flesh. When I have told someone in no uncertain terms that I don’t need them. When I have pushed people away to deal with my wounds in private.

When a donkey has quite literally bitten me on the arm after a drunken night of dancing with a man I knew better than to engage with.

It turns out self-compassion was not, and has never been: Act like you deserve my compassion.

It’s more like:

You’ve been through a lot. You’ve tried a lot of ways to make that okay. Some of those have been messy, and in hindsight, you regret them. That’s what humans do sometimes. It’s okay. You’re allowed to make mistakes, you’re allowed to change your mind, you’re allowed to make new decisions when new information presents itself. You don’t need to punish yourself for what you couldn’t have known before you knew it.

What you are holding is heavy. Be gentle.

Even if you bite me, even if you kick and scream, even if you never let me hold you, we are on the same planet right now. You are not alone. I see you. And I’m so, so sorry.

Sources:

“Black-Faced Spider Monkey,“ New England Primate Conservancy

“Exploring the Meaning of Self-Compassion,” Self-Compassion, Dr. Kristin Neff

“Black Spider Monkey,” World Wildlife Fund

“The Social Primate,“ Primate Rescue Center